News & Blogs

Continuing the previous post on Japanese traditional New Year dishes, we talk about the background of world-famous food, "mochi (餅)."

What is "mochi" again?

Kagami-mochi (鏡餅) – Mirror-like mochi offered to the deity.

Ozoni (お雑煮) – Human dishes with local flavors.

Sweet mochi goes international.

In this blog, we touch on diverse topics about Japanese food cultures, practices together with the culinary secret, TREHA®, and its important role in the Japanese food industry. We hope our blog helps you obtain in-depth knowledge of the secrets and science behind Japanese cuisine, shared from our kitchen, to yours.

Mochi - Another Japanese traditional New Year food

The Japanese celebrate the New Year by welcoming the deity of the year (歳神様 Toshigami-sama), a god of harvest who is believed to visit each house on the first day of a year to gift prosperity, happiness, and health. In the previous post, we introduced the New Year's dishes, osechi-ryori. "Mochi,” rice cake is another New Year’s food that is just as important. As many of you know, rice cake is made with steamed glutinous rice. The freshly cooked rice gets mashed with a mortar and a pestle until it becomes smooth, sticky, and shaped into appropriate sizes.

Mochi emerged around the Yayoi period (around the 5th century BC - the middle of 3rd century AD) when rice cultivation was introduced, and its steaming method became widespread for cooking. Since ancient times, mochi has been considered sacred food holding the spiritual power of the rice deity. The Japanese put effort into preparing mochi as unique offerings to the gods rather than rice as raw material. In addition, it has been believed that mochi empowers and regenerates lives. Therefore, mochi is freshly prepared and offered to the deities on festive days and seasonal celebrations in addition to the New Year.

Although New Year's mochi is generally made on December 28th, households that pound mochi with a pestle and a mortar are declining in numbers. Purchasing mochi at supermarkets is becoming more prevalent. Nevertheless, various organizations often host mochi-pounding events involving teamwork spirit, a sense of achievement, and freshly pounded mochi, a crowd magnet. Preschools and elementary schools organize the event to teach children Japanese traditions, community associations host it for social gatherings, and shopping malls make it a big promotion to attract shoppers.

Round mirror-shaped mochi (鏡餅 kagami-mochi) for offerings to the deity.

There are two types of mochi that represent the New Year.

One is kagami-mochi (mirror rice cake鏡餅), which consists of two layers of round mochi offered to the deity of the year, who visits each household on New Year's Day to bring happiness and prosperity. The bottom mochi is larger than the one sitting on it. Even though there are various theories of the origin of the name, the most prominent belief is that the round mochi acting as a mirror is where the deity stays during the first seven days of the New Year. Two pieces of different-sized mochi symbolize a wish for stacking another healthy and sound year on the previous year. Kagami-mochi is beautifully decorated with other items to respect the spiritual guest. Naturally, each decoration has meaning. Let us introduce the classic decorations.

Bitter orange or mandarin orange:"daidai (橙) or mikan (みかん)."

Since ancient times, "bitter orange" has been the miraculous fruit of immortality. Also, since "bitter orange (橙 daidai)" is pronounced the same as "successive generations (代々 daidai),” it signifies a wish for the family line to continue for generations. These days, mandarin orange is often used as a substitute.

Sacred paper strips: "Gohei (御幣).”

The paper stripes in red and white are placed under the mochi. Red is a talisman color. White represents the boundary between the world and the realm of the sacred deities.

Sacred paper mat: "Shiho-beni (四方紅).”

Square paper with red borders on all sides, indicating a pray to all directions of the earth and above for the year’s prosperity.

Wood stand with a square pedestal: "Sanpo (三方).”

A small wooden stand featuring holes on three sides is used for placing an offering to the deities.

Kagami-mochi prepared at the end of the year is displayed on the Kamidana (神棚, a special shelf dedicated to the spirits) or in Tokonoma (the Japanese style alcove in the reception room where items of art or essential significance are displayed such as calligraphy or family heirloom.) If no Kamidana or Tokonoma is at home, kagami-mochi is placed in a clean and pleasant space where the deity feels comfortable and welcome, such as a high place in the living room or the entrance.

Although it varies by region, the kagami-mochi is taken down around January 11th and eaten by the whole family to wish for the year’s health and prosperity through the deity’s energy. The ceremony is called kagami-biraki (鏡開き), meaning the opening of the mirrors. Slashing kagami-mochi with a knife is contraindicated because it recalls hara-kiri. Alternatively, mochi is broken into pieces by hand or a mallet. The wording for the event also matters, which is called “opening” mochi instead of “breaking” mochi because breaking the mirror is bad luck, whereas the opening of the mirror is good luck.

Since mochi becomes stone-hard after being displayed during the New Year’s celebration period, it would be soaked in hot water for a while to soften. The kagami-mochi pieces are often added to the sweet red-bean soup to make a dish called shiruko or zenzai.

Kagami-mochi for a deity, ozoni for a human.

Another type of mochi that represents the Japanese New Year is ozoni (お雑煮). Ozoni is a dish featuring mochi and soup made by fish broth seasoned with soy sauce or miso paste. The Japanese eat ozoni on New Year's Day to pray for a safe and sound year.

As mentioned, mochi was initially an offering to the deities, so it has long been dedicated to ceremonial occasions. Ozoni developed as strew containing mochi, taro roots, carrots, and daikon radishes offered to the deity before Year’s Day cooked in the water procured from a well or river first time in a year, called “Wakamizu (young water).” It is believed such food items are brimmed with the deity’s energy to revitalize humans.

Ozoni reflects the food culture of each region. It is no exaggeration to say the only standard format is mochi being served in a soup across different areas throughout Japan. The hometown of one’s or one’s parents is easily identifiable based on what kind of ozoni the person grew up eating. Now, let us introduce variations of ozoni.

Round-shaped mochi (丸餅 marumochi), which is the original shape, is prevalent in the Kansai region (the southern-central region of Japan). In contrast, rectangular-shaped mochi (角餅 kakumochi) is consumed in the Kanto region (the Greater Tokyo Area) and cold areas.

The difference in shape emerged because the population in the Kanto region in the Edo period (17th-19th centuries) snowballed, requiring a more efficient mass production method of mochi. A large mochi sheet was cut into smaller pieces rather than individually rolled by hand. People are stuck with the familiar shape despite the modern luxury of choice between round or rectangular shapes. People in the Kansai area particularly appreciate the round mochi because the form means peacefulness. In Kagawa and Ehime prefectures in the Shikoku Island, mochi filled with sweet red bean paste is used in ozoni, a savory dish. Mochi shows its variation in shapes and cooking methods such as baking or boiling.

The soup identifies the locality. Kyoto-style (Kansai-style) ozoni contains soup stock made from kelp and dried bonito flakes seasoned with white miso paste, presenting its iconic white appearance. In contrast, the clear soup of kelp and dried bonito stock seasoned with soy sauce is predominant in the country, excluding the greater Osaka area.

As far as toppings go, fresh produce and catch exhibit the local taste besides classic toppings, including radishes, carrots, and green onions. Good examples are edible wild plants and mushrooms in the North-Eastern Parts, salmon fillet and roe in Niigata prefecture, green laver in Chiba prefecture, nori and clams in Shimane prefecture, and oysters in Hiroshima prefecture.

Japanese mustard spinach and chicken are often used in the Kanto area, heavily influenced by the samurai culture and values. The abbreviated name of those food combinations signifies "gaining fame (名取り natori),” which is the interpretation of “gaining the severed head of an enemy general.” On the other hand, in Kyoto, which was once the Capital of Japan, a big piece of taro root, called “kashira imo,” is added to ozoni, wishing to achieve a leading role in the society.

I grew up eating ozoni with baked rectangular-shaped mochi topped with chicken and Japanese parsley in a clear soup. When I first had Kansai-style ozoni made with white miso paste at my grandparents' house in Osaka, I was surprised by the difference, especially the soup’s sweetness. There was another surprise when I first had ozoni with yellowtail instead of chicken, with unbaked mochi. They were the moments that made me realize the food culture is quite different even though Japan is a small island country.

Mochi-gashi is a sweet mochi dessert (and snack)

In the beginning, I explained that "mochi" is made with steamed glutinous being mashed until smooth and sticky. In the world of Japanese-style confectionery, any pieces with a soft and elastic texture are called mochi. It doesn’t matter if it is made out of mochi, glutinous rice powder, or joshinko (powdered non-glutinous rice).

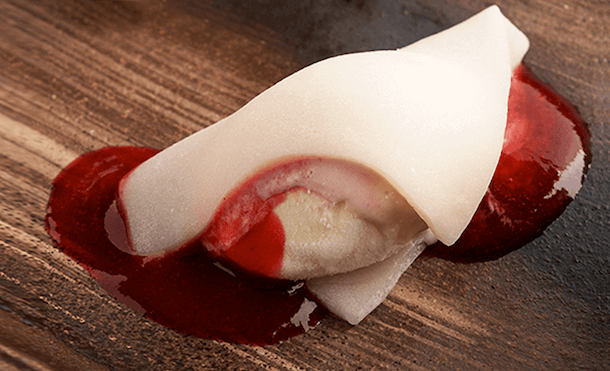

The world-famous "Mochi ice cream" and "Daifuku” are also mochi-gashi. Mochi ice cream, launched in Japan in 1981, has evolved into colorful and “instagrammable” sweets in the actual and virtual worlds 40 decades later.

You can find a recipe for Strawberry Mochi Ice Cream Wraps from here. Although it takes some practice to handle sticky mochi dough, you will find various uses once you get the hang of it, including non-gluten mochi crepes and mochi topping.

The next time you eat or make mochi ice cream, we hope you remember mochi was initially a ceremonial food offered to spiritual beings.

Did you find this blog interesting?

Please share it with your friends in the food service industry.

We regularly update the blog about the food culture of Japan, where TREHA® was discovered for culinary applications.

Click here and send us a message to subscribe.

Or hit us up on Instagram @trehalose_sensei!

You might also be interested in:

Japanese traditional food series 2: Chitose Ame, candy for healthy longevity (千歳飴)

Japanese traditional food series 3: Yuzu (柚子) and the winter solstice

Japanese traditional food series 4: Noodles on New Year's Eve (年越しそば)

Japanese traditional food series 5: Japanese traditional New Year’s dishes, Osechi-ryori (おせち料理)

Japanese traditional food series 13: Inari sushi offered to a deity of harvests