News & Blogs

What is "Dashi (出汁)?

Why and how did Dashi culture develop?

The evolution of Dashi and cultural background.

Why does Kanto (East Japan) use bonito flakes, and Kansai (West Japan) uses kelp?

How to prepare delicious dashi (出汁) stock

In this blog, we touch on diverse topics about Japanese food cultures, practices together with the culinary secret, TREHA®, and its important role in the Japanese food industry. We hope our blog helps you obtain in-depth knowledge of the secrets and science behind Japanese cuisine, shared from our kitchen, to yours.

What is "dashi (出汁)"?

Dashi (出汁) is a soup stock that is regularly used in Japanese cuisine to add sweet, sour, bitter, and salty flavors and umami. Dashi is made by extracting single or combined ingredient(s) such as dried bonito flakes (鰹節 katsuobushi), kelp (昆布 kombu), dried sardines (煮干し niboshi), dried shiitake mushrooms, vegetables, and the bony parts of a fish in boiling water.

Dashi stock is the foundation of flavoring in Japanese cuisine. Miso soup is the best example, but Dashi is also used in all other dishes, including simmered dishes beyond the iconic miso soup. Even an informal food like okonomiyaki (savory pancake お好み焼き) could call for Dashi.

In other words, Dashi stock can be described as a critical element characterizing Japanese cuisine or the essential foundation of Japanese cuisine. A typical soup stock in the culinary world known as “broth” is made by boiling meat-based ingredients, utilizing the fat content in addition to the umami from the raw materials. On the other hand, Dashi is a product of the Japanese unparalleled cooking method, which season dishes with umami without depending on fat while enhancing the ingredients’ original flavor.

Dashi culture was developed by Japanese folk religion and water quality.

As mentioned above, various items are used to make Dashi, including dried bonito flakes, kelp, dried sardines, dried shiitake mushrooms, and more. Japan is privileged by natural food sources such as oceans and mountains, providing easy access to such ingredients. Although this is the main factor behind the Japanese Dashi culture, there are two other reasons Dashi culture flourished in the country.

1. Custom to avoid meat consumption

Livestock or animal consumption was very little until the early Edo period (the 17th century) because the Japanese historically valued and protected animals supporting rice cultivation. In the Nara period (the 8th century), Buddhism further fortified the custom by prohibiting eating animals. Eventually, the Japanese came to consider meat-eating defilement. Thus, the main ingredients of the Japanese diet gradually shifted to grains (mainly rice), vegetables, and seafood. It is believed that Dashi emerged in response to this change to enhance umami in meals.

2. Soft water and Dashi

While water comes in hard and soft, water in Japan is generally soft. When Dashi is prepared using hard water, the minerals interfere with extracting the umami components of inosinic acid and glutamic acid. In addition, such minerals bind with amino acids, causing filming on the surface of the soup stock. In contrast, Japan’s soft water with fewer minerals efficiently extracts umami, allowing cooks to make Dashi from a wide range of ingredients. The natural environment in Japan is best fitted for Dashi culture to grow more than any other country.

The history of Dashi is as profound as the soup stock itself.

Among many varieties, the most well-known types are probably "bonito (Katsuo 鰹)” and "kelp (Kombu 昆布),” which boast a long history. The descriptions about such Dashi varieties were mentioned in the literature around 700 AD, more than 1000 years ago, and the content clearly explains how much they were treasured. Interestingly, the word "Dashi" was not found in this literature at this point.

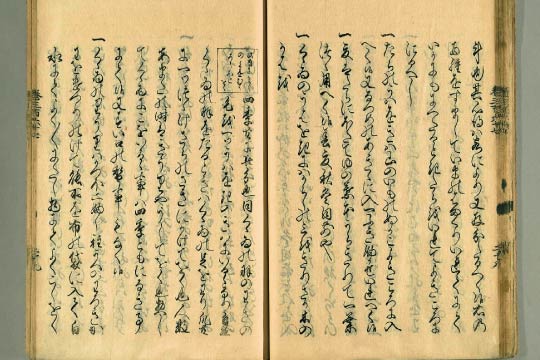

The oldest description of Dashi can be found in the cookbook (pictured below), estimated to be written in the late Muromachi period (1336 to 1573), which teaches how to prepare and cook fish and birds besides table manners. The book includes the description of filter bags used to obtain Dashi stock from dried bonito flakes and kelp when cooking swan.

In the Edo period (1603-1868), descriptions of Dashi began to appear in various literature. For example, "Ryori Monogatari (料理物語 Story of Cooking)," considered the first Japanese practical cookbook, refers to niban (second brew) dashi. In addition, the use of kelp as a Dashi material is mentioned.

Later on, the mid-17th century’s literature indicates a stock made with kelp and dried bonito flakes. It can be assumed that the Japanese had discovered that a combination of two ingredients could enhance the umami.

In the same period, soba (buckwheat) noodles prevailed in Edo (current Tokyo), while udon noodles became popular in the Kansai region (Greater Osaka area). Such soup noodles helped Dashi permeate Japanese society even more. Since kelp and dried bonito were luxuries back then, they were out of reach for the commoners. Considering high-quality dried kelp and bonito flakes are very expensive as of today, they must have been treated like today’s caviar or truffles.

A cookbook published in 1893 suggests katsuo (bonito flake) dashi for daily consumed soups while recommending a combination of bonito flakes and kelp to make a clear soup (澄まし汁 sumashi-jiru) for special occasions, which proves that combined Dashi was commonly used.

Bonito flakes for Kanto (East Japan) and kelp for Kansai (West Japan)

Regional preference for Dashi is represented by Kanto (the Greater Tokyo Area) style and Kansai (the Greater Osaka Area) style, as described in the tempura article. In the Kanto region, Dashi is made primarily from dried bonito flakes, while in the Kansai region, it is made mainly from kelp. The ocean logistics and the difference in water quality explain these regional preferences.

1. The distribution channel of kelp

In the 17th century, kelp was mainly transported from Hokkaido to Osaka via the Sea of Japan on the westbound route because the eastbound route from Hokkaido to Tokyo through the Pacific Ocean was more difficult for ships of the time to sail against the Black Current heading to the north. Under this logistic circumstance, top-quality kelp was depleted by purchasers in Osaka, and the remainder was transported to Tokyo for consumption. (See the map below). Therefore, kombu (kelp) dashi did not permeate in Kanto (East Japan) compared to Kansai (West Japan).

2. Impact of water quality

Even within Japan, where water is generally soft, mineral content in Kansai water is lower than Kanto water, making it more suitable for kombu (kelp) dashi. For this reason, dried bonito flakes are mainly used in the Kanto region, creating a bold-flavored Dashi.

In addition, I speculate that the plant-derived kombu (kelp) dashi might have been preferred in the Kansai region due to the many Buddhist temples where monks were prohibited from consuming animal-based food.

How to prepare delicious Dashi (出汁)

We would like to share how to prepare three common types of Dashi: katsuo dashi (dried bonito flakes), kombu dashi (kelp), and combined dashi (awase dashi) using bonito flakes and kelp.

1. Katsuo dashi (dried bonito flakes 鰹出汁)

When making katsuo dashi, use about 1oz (30g) of dried bonito flakes per 1qt (1L) water.

First, bring a pot of water to a boil, then turn off the heat. Sprinkle the bonito flakes and wait for a minute or two without stirring.

Gently pour the stock through a fine-mesh strainer over a bowl, let it stand for about a minute, and lift the strainer to complete ichiban (the first brewed) dashi. When straining the soup through a strainer, be careful not to squeeze or press the bonito flakes, as this will make it taste harsh.

2. Kombu dashi (kelp 昆布出汁)

When making kombu dashi stock, use about 2/7oz (10g) of dried kelp per 1qt (1L) water.

First, wipe the surface of the kelp lightly with a moist cloth to remove any dirt. It is recommended to soak the kelp in water for 30 minutes to an hour, making it easier to release the umami components.

Place the water and kelp in a pot over medium heat, and turn off the heat just before it comes to a boil (about 175℉/80℃). The key is to turn off the heat when the bubbles start to rise slightly from the bottom of the pot, as boiling will cause off-tastes and a slimy texture. When bottled water is used, soft water is recommended.

3. Combined dashi (awase dashi) of bonito flakes and kelp

When making awase dashi stock, use about 2/7oz (10g) of dried kelp and 4/7oz (20g) of dried bonito flakes per 1qt (1L) water.

First, wipe the surface of the kelp lightly with a moist cloth to remove any dirt. Before making Dashi, it is recommended to soak the kelp in water for 30 minutes to an hour, making it easier to release the umami components.

Place the water and kelp in a pot over medium heat, turn off the heat just before it comes to a boil (about 175℉/80℃). Remove the kelp, sprinkle the bonito flakes, and wait for a minute or two without stirring them.

Gently pour the mixture into a fine-mesh strainer over a bowl, leave it for a minute or two, and then gently squeeze the bonito flakes. (Be careful not to burn yourself.)

In Asian supermarkets, you can find granulated Japanese Dashi or Dashi packs containing dried bonito flakes and kelp in a small sachet, which might be helpful. These days, Japanese Dashi is frequently used in Western cuisine.

What kind of dishes would you like to create using Japanese Dashi stock?

Did you find this blog interesting?

Please share it with your friends in the food service industry.

We regularly update the blog about the food culture of Japan, where TREHA® was discovered for culinary applications.

Click here and send us a message to subscribe.

Or hit us up on Instagram @trehalose_sensei!

You might also be interested in the following articles:

Exclusive interview with Chef Meguro, the authentic Edomae sushi master in Tokyo

Exclusive interview with Chef Shimomura, the executive chef of a MICHELIN Plate Japanese cuisine restaurant in Yokohama

Shinto religion and Japanese cuisine (washoku 和食)

B-class Gourmet, an undervalued variety of Japanese cuisine

Samurais like it hot!? A story of tempura

Japanese traditional New Year’s dishes, Osechi-ryori (おせち料理)

For the Japanese, “Nigiri” comes to mind when you say sushi